Fluorite from Weisseck, Austria

The Weisseck summit cleft, Lungau, Salzburg

The Weisseck, 2.711m high; its summit is an alpine wasteland, the landscape conveys loneliness and vastness as well as unspoiled beauty.

It is located in the southeasternmost region of Salzburg, the Lungau. Stretching over an approximately 1.000 km² plateau, the region is surrounded by the Lower Tauerns to the north and west, the Hohe Tauerns to the southwest and the Gurktaler Alps to the south. Following the Zederhaus Valley to its end, the Rieding Valley then branches off to the west. In the north the Mosermandlrises; in the south towers the summit of the Weisseck.

Its fluorite deposits were described as early as 1859 by Dr. Ludwig Ritter von Köchel in his book "The Minerals of the Duchy of Salzburg". Historical crystals from classic discoveries of that time can be found in display cases and drawers of old Austrian natural history museums. Some are labeled Königsstuhlhorn, Rauris - a designation that even von Köchel doubted.

Through the centuries, time and again cavities were opened in the visible limestone and dolomitic marble of Weisseck, and remarkable discoveries were made. In the 80s, a find at Lake Rieding (Fig. 2) by a group of Viennese collectors resulted in minor celebrity; on the eastern slope a discovery with blue fluorite provoked a stir among insiders. The deposits are rich, the finds varied, but this article focuses on the most significant discovery at Weisseck: the summit cleft.

fig. 1: Lake Rieding in the morning

fig. 2: superb Fuorite from Lake Rieding

The history and development of the summit cleft has already been covered in the magazines Mineralienwelt and most recently inMineralogical Record, and is therefore only briefly outlined.

In 1996, the two Lungauer collectors Walter Petzelberger and Martin Brunnthaler were working at a site located about 50 meters below the summit. The site had long been known and leads approximately 6-7 meters deep into the mountain. The two discovered indications, but since they were busy with other projects, they let it rest until the year 2000. Then, however, it became quickly apparent that there was a significant finding and they brought on more collectors, including one of the main players on theWeisseck, my friend and partner Reinhold Bacher, the chairman of the Lungau Chapter of the United Mineral Collectors of Austria.

After the group broke up due to internal strife, individuals and small teams worked on and pushed 47 meters deep into the mountain. They found fluorite in unbelievably diverse forms, various accompanying minerals, and a variety of colors that earned the deposits international importance. The bitter aftertaste is that decades-long friendships were destroyed in the face of the discoveries, and that old mountain-mates developed into bitter enemies.

It was a late summer day in August 2009, when I again set off with Reinhold for the summit cleft. In the early hours of the morning we were already on the way through the Mur Valley, past the old Arsenhaus; investing three euros there allows you to pass through a barrier and drive up to the Murritzen parking lot. At this point, a second barrier prevents any further driving.

We completed a one-hour march along a forest road to the Stickler Hut (Fig. 3). Here a trail led us along the south side to theRieding Gap. Although in the valley bathing temperatures still prevailed, we were dressed in long underpants, hoods and thick jackets and the hour-and-a-half climb brought sweat to our brows. But as we reached the ridge and left the sheltered southern side below us, an icy wind slapped us in the face (Fig. 4).

fig. 3: Strickler hut

fig 4: Rieding-gap

Before us, a majestic sight surrounded on three sides by rugged cliffs, behind it a fantastic mountain panorama: Lake Rieding. We were now on the Rieding Ridge; the sheltered south side lay at our backs and throughout the following one and a half hours an icy north wind blew towards us. The warm clothing paid off from here. The climb now became steeper. Finally in the last few meters before the summit (Fig. 5) we found ourselves again on a flat, wide trail. To the south and east steep flanks ran down, referred to by the locals simply as “hell” (Fig. 6).

fig. 5: the author at the summit

fig. 6: the "hell" at the north-east side of Weisseck mountain

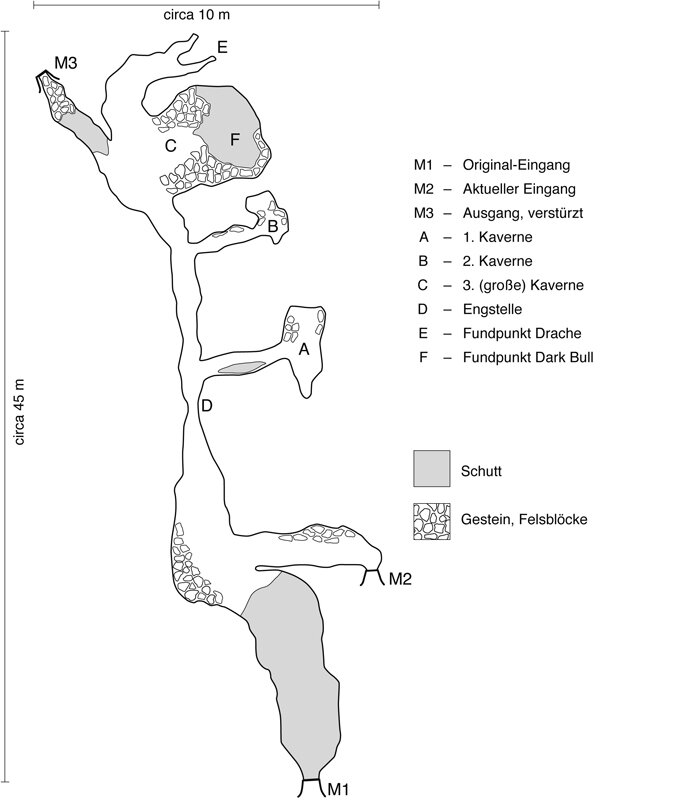

In this area we now climbed up along the southern slope and reached about 50 meters below the site (M1 on the map) where the cleft was entered in 1996. Through their work the Strahlers had arrived back at the surface (M2 on the map) and had taken advantage of the space between the two entrances as a depot for the accumulating debris. M1 is therefore inaccessible today, but the site offers sufficient space to deposit backpacks and get changed.

map of the Weisseck summit-cleft

In suitable cleft clothing and equipped with helmet and headlamp, we climbed up to M2 and advanced into the crevice. Shortly after the start we had to get on our knees, then on our bellies crawling forward. Reinhold and I reached a narrow spot at which the passage was very narrow and low. In this location exceptional and beautiful specimens had been found, on which individual or small groups of fluorite sit on needle quartz. The crystals had light blue outer zones and dark purple zonal structure. The quartz was coated with a brown iron layer. Unfortunately, only a handful of these unique pieces were found (Fig. 7). The material was extremely brittle, the deposit very limited. The explorers had made it to this point in their first year. The passage now led us into an angle of about 45 ° uphill.

fig. 7: Fluorite on Quartz-needles

Reinhold and I were still crawling on our bellies, and the hard and sharp rocks now made the elbow and knee pads worthwhile. Every movement was painful, exhausting; breathing was difficult.

The helmet lamps lit only the area immediately in front of us; the tightness was physically and mentally perceptible, until we finally reached the first crossway, which offered a little more space and freedom of movement.

At the end of that passage W. Petzelberger had been able to open a 2m deep and 1.5m high cavern in the second year of work, in which particularly dark, sharp-edged cubes were found. Through tectonic shocks, many crystals here had been freed and therefore were quite damaged.

At this point we had managed the first 15m; the next 7-8m we again had to crawl. Years before these meters brought the collectors beautiful crystals, which had been carried outwards by infiltrating water (Fig. 8). The Strahlers transported the debris in small plastic containers - the front man filled them, pushed them along his body to the back, and passed them on to the man behind him. In this primitive way, many tons of rubble were taken outside or stored in other parts of the cleft.

fig. 8: beautiful Fluorites carried outward by infiltrating water

fig. 9: sharpe edged fluorites

We now passed another side passage. Here Reinhold discovered the second cavern in June 2006. Its fluorite differed from the other crystals of the summit cleft through their much lighter bluish color and the distinct zonal structure with a light blue outer zone and a purple core. The structure is very plastic and consists of grown-together sharp-edged cubes (Fig. 9).

Now followed one last steep creeping incline; in the spring of 2003 it was cleared of fallen rocks, behind which lay the endpoint of the gap: the great cavern, over 8m deep, up to 3m wide and 1m high. The opening 3 shown on the map has since collapsed in on itself (Fig. 10).

Now we found ourselves in the treasury, where even today you can see the number of fluorite rock bands clearly reminiscent of past findings.

If your eyes fall on the richness of color, you will truly expect to find a real treasure. The findings here were more rich and varied than anywhere else. Classic for the summit cleft are stepped crystals with an edge length up to 15cm. This type was most common, and is also the best known.

fig. 10: "fresh" crystals in a cleft

But there are serious differences in quality. Most crystals show a partially dissolved, coarsely porous surface; less common are those with smooth surfaces, and absolute rarities are crystals with high gloss (Fig. 11). Most of the pieces have some transparency; just a few are of such high quality that with even the slightest light source they reveal a rich play of colors in purple, blue and green-blue.

fig. 11

At this location a special find by R. Bacher must also be mentioned. In 2003 he followed a fluorite band into the ground, came across an enormous vein and uncovered a roughly 50kg crystal. It consisted of 8-9cm long crystals of brilliant quality, was completely undamaged and formed as a floater. In a 7-hour forced march he was able to lug it down to the valley and it is now a showpiece of his collection. He christened the crystal "Dark Bull" (Fig. 12) after a popular energy drink.

fig. 12: dark bull

Furthermore, sharp-edged, almost black cubes were recovered in the large cavern, with excellent surface quality. Particularly noteworthy are three isolated finds of green fluorite, intergrown crystals with stepped edges similar to the purple ones. An exception was an evenly formed 48mm cube. Its intense, almost turquoise color is its most distinctive feature. Since 98% of the finds consist of intergrown crystals, as a single crystal it is an exceptional rarity (Fig. 13).

fig. 13

In addition, nearly spherical aggregates were found in a blue-green color. The same discovery included sharp-edged crystals of up to 3 cm edge length with a matte finish and slightly more greenish color (Fig. 14 and 15).

fig. 14

fig. 15

The rarest find, however, consisted of only three crystals from the rearmost area of the cavern. The best of these is the crystal R.Bacher called "The Dragon". Its body is made of stepped green, highly transparent crystals, the head of a single purple cube, and the back is armored with yellow calcites (Fig. 16).

fig. 16: the dragon

The most common accompanying mineral was calcite, usually heavily diluted in yellowish to brownish color (Fig. 19). Traces of copper minerals such as malachite and azurite were present (Fig. 17). Certainly the visually most attractive are the barite roses, which reached a size of up to about 5mm (Fig. 18).

fig. 17: copper-minerals

fig. 18: Fluorite with Barite-roses

fig. 19

On this day we dug about one and a half meters deep in the third cavern and came upon a collapsed cavity. From this we were able to recover light green, skeletonized fluorite floaters up to 7cm in size; they showed good transparency and excellent color combination in transmitted light. The diversity had been enriched by yet another variant.

The summit region of Weisseck is now strictly protected; only with a special permit are two teams allowed to search the area to find new sites. In the area there are no exceptions to the collection ban, although how well it is observed can only be guessed at this point. The penalties are rigorous and are meant to serve as an example; the area is also strictly monitored. The collection restrictions serve to maintain the sublime landscape, which should not be destroyed by the recklessness of a few.

The summit cleft is now considered exhausted. Of course in the large amounts of debris some good samples might still be found, and with a little luck and an enormous amount of work perhaps a small cavity could be opened up, but the work involved would in no way be proportional to the findings.

The discovery site has given its explorers joys and sorrows, demanded a lot of hard work and supplied world-class fluorite. In the years of work it has shown mercy - all of the collectors have returned safely.

One major disappointment, however, is that Walter Petzelberger did not experience first-hand the renown for his life's discovery, as he passed away in 2008!